Rich clients are becoming increasingly popular nowadays. A quick search through Google on "rich client framework java" returns over 200.000 results.

These frameworks can be divided into 2 distinct categories:

The Swing or SWT based frameworks, designed for out-of-browser applications, to be used with technologies like Java Webstart.

The Rich Internet Application (RIA) frameworks, designed for providing a rich client experience within the confines of a web browser (such as Mozilla or Internet Explorer).

Today, RIA frameworks make up the bulk of the rich client frameworks on the market today. Among these you’ll find names like Flex, Google Web Toolkit, Ice Faces, … Their popularity is mainly caused by the ease of deployment: no installation is needed, almost every user already has a Web browser. If you look at them at an even wider angle, you’ll see that they’re edging closer each day to the spectrum of fully-fledged rich client applications. At that point, Swing’s only disadvantage will be the deployment issues. Due to the server-side nature of some frameworks, you’ll limit your capabilities more than when you’d be using a Swing-based framework.

For Swing (or SWT) based application, the landscape is a bit different. There are only a handful of complete frameworks on the market:

Eclipse RCP, the platform on which the Eclipse IDE has been built

Netbeans RCP, the platform on which the Netbeans IDE has been built

These frameworks are complete platforms, which have proven themselves through their respective IDE’s to showcase their possibilities. However, these possibilities come at a steep cost. With Eclipse RCP, for example, you’ll be straying off the known Swing path and enter the world of SWT, and both don’t play well together. With Netbeans RCP, you’re mostly confined to the Netbeans IDE to do your development (that is, if you want to develop quickly).

Both platforms can be quite cumbersome and come bundled with a complete package. It’s complexity can be overwhelming for a standard Swing developer and does not always promote effective, good programming style.

The Valkyrie RCP framework does not promote itself as a complete platform. Instead, it provides developer a clear and easy way to build enterprise-class applications, without straying too far from the standard, well-known path, whilst ensuring enough flexibility to cope with the difficult issues coupled to the development of enterprise applications. Built on the strong foundations of the Spring Framework, it combines the best practices advocated by the Spring Framework with a component-based abstraction on top of Swing to ease development of Swing rich client applications.

Valkyrie RCP was based on the work done in Spring Rich Client, but emphasizes the use of annotation based configuration. Spring 3.0 provides good support for annotation based configuration and Valkyrie uses these possibilities extensively.

This introduction will try to cover as much ground as possible to let you hit the ground running when starting with a Valkyrie application.

A RCP application in its basic form is quite simple:

An application consists of a application windows, which in most cases contains:

The main content pane

One or more navigational structures, such as a menu bar or a toolbar

A statusbar to show all sorts of messages to the user

These can be augmented with global search fields, help functions or other components that an application might require.

An application window is the foundation on which every rich client is built. Without an application window, you don’t have a place to put the components that make up your screens.

In Valkyrie, the application window is represented by the ApplicationWindow class. The application window builds the visual window component and shows it to the user.

Application windows are not created individually in Valkyrie. A factory pattern, called ApplicationWindowFactory handles instantiation of an application window. This way windows are created in a clear and uniform way throughout the application, without bothering the developer.

In our simple example, you will not find this factory. Valkyrie does not need to have a ApplicationWindowFactory defined. If it is not configured, Valkyrie will fall back on a default implementation within the framework, consisting of a simple view area with a menubar, statusbar and toolbar.

You can, however, define your own application factory. To do this, you just need to implement a ApplicationWindowFactory and override the applicationWindow method in your ApplicationConfig to return an instance of your new class. Valkyrie will pick up the class and use it instead of the default implementation.

You can for example create an application window factory that leaves out the toolbar, but creates an outlook-like bar or task-pane oriented navigation on the left side instead. You can find an example of this in the dataeditor example.

Application windows are containers for views. A view can be seen as an individual window representing a specific state within the application.

Views are the main view area of your applications and will contain the bulk of the user interaction, unless you’ve chosen for a dialog-based approach. You can for example have a flow of views representing a process within your application, or a view containing a table which, when double-clicked, shows a detail of the selected item.

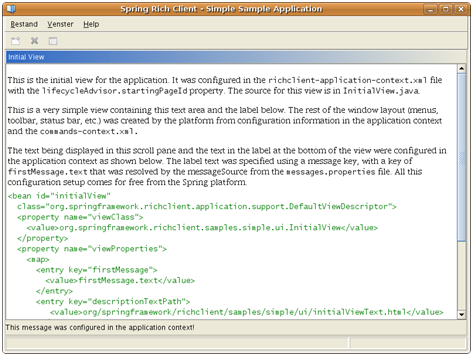

In our first example, a view shows a HTML file together with a message from a resource bundle.

Implementing a view is quite simple. When viewing the example view, you’ll see this:

public class InitialView extends AbstractView {

// omitted for brevity...

/**

* Create the actual UI control for this view. It will be placed into the window according to the layout of

* the page holding this view.

*/

protected JComponent createControl() {

// In this view, we're just going to use standard Swing to place a

// few controls.

// The location of the text to display has been set as a Resource in the

// property descriptionTextPath. So, use that resource to obtain a URL

// and set that as the page for the text pane.

JTextPane textPane = new JTextPane();

JScrollPane spDescription = getComponentFactory().createScrollPane(textPane);

try {

textPane.setPage(getDescriptionTextPath().getURL());

}

catch (IOException e) {

throw new RuntimeException("Unable to load description URL", e);

}

JLabel lblMessage = getComponentFactory().createLabel(getFirstMessage());

lblMessage.setBorder(BorderFactory.createEmptyBorder(5, 0, 5, 0));

JPanel panel = getComponentFactory().createPanel(new BorderLayout());

panel.add(spDescription);

panel.add(lblMessage, BorderLayout.SOUTH);

return panel;

}

}

AbstractView mandates that you implement the createControl method. This method can deliver any JComponent to show its contents. In most cases, this will be some sort of container or panel.

The entire menu bar system and derived navigational structures are command based. In essence, this means you’ll never make a JMenu or JMenuItem manually again. Ever. Simply put, you’ll create a command, which contains code that needs to be executed (for example, change a view or print the current selected item). Valkyrie will handle the creation of the visual components and couple the command behavior to the visual component’s behavior.

In Valkyrie, the command context is a separate context that needs to be defined in the main application context lifecycle.

In our example, the command configuration looks like this:

@Configuration

public class SimpleSampleCommandConfig extends AbstractCommandConfig {

@Bean

@Qualifier("menubar")

public CommandGroup menuBarCommandGroup() {

CommandGroupFactoryBean menuFactory = new CommandGroupFactoryBean();

menuFactory.setGroupId("menu");

return menuFactory.getCommandGroup();

}

@Bean

@Qualifier("toolbar")

public CommandGroup toolBarCommandGroup() {

CommandGroupFactoryBean toolbarFactory = new CommandGroupFactoryBean();

toolbarFactory.setGroupId("toolbar");

return toolbarFactory.getCommandGroup();

}

}

A basic command context expects the configuration of a toolbar and a menubar. Commands can be added to those bars.

Internationalizing your application can be quite an important part of your work, and sometimes also one of the most time-consuming too.

Valkyrie supports internationalization through resource bundles defined in the application context (see the messageSource bean). For example, Valkyrie provides a mechanism to set the title of your application through the application descriptor. If you set the key applicationDescriptor.title to some value, that value will show up as the title of your application. Messages are found through a MessageSource implementation, for which the resource bundle implementation is perhaps the most widely used.

The same is true for application icons and images in general. The key applicationDescriptor.icon sets the application’s icon. Like messages, the images are found through an ImageSource, which contains property files with the keys and the images that go with the keys, and the location where the images can be found (in the jar for example, or somewhere else).

Valkyrie also contains other components to make rich client programming easier. A form framework that handles easy form creation, undo functionality and validation. Exception handling to show visually attractive messages when your application goes down the drain. A wizard framework to make data input for the not-so-tech-savvy users simpler and much more.

We’ll discuss these in detail later.